“There is no doubting the authenticity of Carvalho’s vision and the originality and severity of her voice.” ―Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Review of Books

For ten years Dora has ritualistically mourned her husband's death, a pointless ritual that forced her to rely on support from old friends and acquaintances. Her beloved husband, a “Christ” so principled he rejected any ambition whatsoever as a construct of a corrupt society, succeeded only in leaving Dora and their daughter with nothing. When her mother-in-law reveals a shattering secret about their marriage one night, Dora’s narrative of her own life is destroyed. Three generations of women―Dora, her daughter, and mother-in-law―must navigate a world that has been shaped by the blundering men off in the distance, figures barely present who nonetheless define the lives of the women they would call mother, wife, or lover.

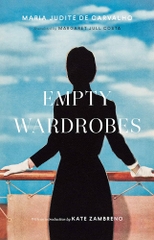

Narrated through the gritted teeth of an acquaintance, Empty Wardrobes―Maria Judite de Carvalho’s cutting 1966 novel, translated from Portuguese for the first time by Margaret Jull Costa and introduced by Kate Zambreno―is a tale of women who are trapped within the quiet devastation of a patriarchal society and preyed upon by the ambient savageries that perch in its every crevice.

“Empty Wardrobes will give you a sense of domestic life under the dictatorship: In precise, unsentimental prose, it tells the story of three generations of women overshadowed by the death of a patriarch.” —Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida, New York Times

“Executed as precisely and without sentiment as an autopsy…There is no doubting the authenticity of Carvalho’s vision and the originality and severity of her voice, as scathing and pitiless in her depiction of ‘empty’ women as in her depiction of oafish swaggering machismo.” —Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Review of Books

“A book about how men betray women, and how women betray each other…a work that does not hesitate to expose the cruelties and power grabs that lie beneath marriage, and how quickly society discards aging women.” —Rhian Sasseen, The Paris Review

“The specter of the patriarchy looms over this mid-20th century tale like depression itself. With the astringent wit of Natalia Ginzburg, Empty Wardrobes is a spellbinding book of domestic disorder that sparks with bitterness and humor.” —Lauren LeBlanc, Observer

“Margaret Jull Costa’s translation hits not a single false note. The text has an antique finish without being dated…The novella manages to cast the eye of a worried oracle on an entire nation.” —Asymptote

“Translated from Portuguese by the award-winning and prolific translator Margaret Jull Costa, the novel is rendered in clear, finely-wrought prose. Not a single word feels wasted or misplaced. …one of those rare, transcendent works.” —The Rupture

“The first by this towering Portuguese novelist to be translated into English…A still, luminous book whose precise characters evoke broad truths about the human experience.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Sharp…This unearthed story leaves readers with much to chew on.” —Publishers Weekly

"Gracefully translated by Margaret Jull Costa, Dora’s story is illuminating, inspiring, and heartbreaking in equal measures. Fans of Anne Tyler, Marian Keyes, and Christine Féret-Fleury will find themselves absorbed in the novella’s sparse but evocative prose." —Booklist

“Its timeliness is both enlightening and depressing…this novel shows us women who see their restraints but struggle to reach beyond the men and political institutions that uphold them.” —Monica Cardenas, Litro Magazine

“A remarkable, necessary novel about women disposed of by men, about isolation and suspension and damage, with an acute perceptiveness that will pierce your mind. Dora, Manuela, Ana, Júlia, Lisa. These women will remain long after the middling men who have abandoned them fade away, as will Empty Wardrobes, finally, thankfully, translated into English.” —Amina Cain, author of Indelicacy

“A compact, merciless tragedy… I read this novel with something resembling a rapturous grief, as if I couldn’t believe this consciousness had finally been rendered in literature, the consciousness of so many women familiar yet unknowable, no longer muted, not saturated with sanctimony but alive, alive with rage transmuting disdain into hilarity by sheer force, alive with intense paroxysms of sadness.” —from the introduction by Kate Zambreno